by Barbara Bryant and Ethan Childs (Navigation Games)

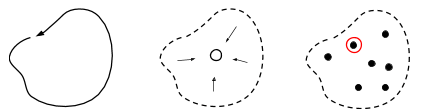

Graphical abstract of Lesson 1: Boundary, Gathering, and Direction-Giving

This spring (2019), we will be piloting a four-lesson third-grade curriculum in seven Cambridge, MA, public schools. Because many children struggle with map interpretation, the lessons build up slowly to map reading. We also bring in many aspects of orienteering that do not require a map, such as running in terrain, knowing the boundary of the area of play, giving and following instructions about where to go, building a mental map of an area by exploring it, visiting checkpoints in order, and being timed. Above all, we want to keep the children moving and having fun.

Our constraints included:

- Four 45-minute classes

- Minimal set-up on the part of the teacher

- Use materials accessible to any gym teacher, with timing equipment optional

- No need for specialized orienteering knowledge on the part of the teacher

- Be able to deliver the content indoors on days with bad weather

- A wide range of physical and mental abilities and types

Each lesson is documented with SHAPE America standards, objectives, materials, set-up, language for introducing the activity to students, a description of the activities, and suggestions for a wrap-up discussion. The teachers are given a written copy of the lesson plans. We introduced the lesson plans to teachers in a 45-minute workshop. The workshop started by throwing the teachers immediately into activities: the boundary run and Animal-O. Then we had a conversation about the sport of orienteering and the goals of the curriculum. We finished by arranging the detailed logistics, including the dates and times of the classes, and indoor and outdoor spaces.

During the spring, Navigation Games staff will attend every PE class (54 in total), in order to support the teacher, with the idea that the program will operate independently of us (should they so choose) starting next year. We will gather feedback on the lessons, refine them, and publish them over the summer.

The four lessons have the following topics:

- Boundary, gathering, and clues

- Building a mental map (Animal Orienteering)

- Introducing the map (Animal Orienteering with a map)

- Racing on a simple map

Below are some notes we gave the teachers:

Safety

In orienteering, participants travel outdoors, over an area that eventually includes locations that are outside the view of the teacher. It’s important that children know and can recognize the boundary of the area in which the games are played, so that the notion of boundaries and safe movement becomes ingrained as the area increases over sessions and years.

Students must also be able to return to the teacher on a signal in order to keep track of everyone, make sure no one is lost or hurt, and to provide necessary instruction and information.

Treating each other with respect and care is important as well. With a particular skill, some students will excel while others may struggle, and it’s important for students on either end of the spectrum to work together for success. Students need also be aware of the environment around them to avoid physically running into objects such as trees and rocks, as well as one another.

Observation and Mindfulness

Orienteering is an excellent way for students to practice observation and mindfulness. Being observant of one’s surroundings is a simple necessity for all movement sports, and orienteering includes an added layer of interpreting the map and surroundings, and making small and large decisions about navigating through terrain.

In order to improve, athletes develop an awareness of how their physical and emotional state will affect their performance. When they make mistakes or have trouble finding a checkpoint, they have an opportunity to review why the mistake occurred, and reflect on how they can try things differently in order to improve.

These lessons are designed so that students who are successful have the opportunity to help their classmates improve. As part of this, students must actively listen to and observe their classmates to understand their needs, and be able to address those needs based on their own experiences. Not only do they experience their own success, but they also experience the feeling of helping others succeed.

Roles

By using and naming roles, the activities keep children busy and engaged even when they are done with their own course. Including the “Helper” role distributes the responsibility away from the teacher, and helps to ensure every child gains competence in the skills being learned. Both teacher and students should have an explicit goal of making sure that everyone in the class understands the material and achieves success. Having explicitly named roles provides a shortcut in explaining the games, as the roles are used over and over again in different games.

- Finder — Synonyms: Runner, Orienteer, Participant, Athlete

- Hider — Synonyms: Course Setter, Game Designer

- Finding opportunities to give children the chance to design the game is a great way to engage them more fully.

- Clue-Giver — Synonyms: Direction Giver, Map, Dispatcher

- Helper — Synonyms: Teacher, Coach.

- The Helper gets consent before helping a Finder. The Finder may refuse help in order to accomplish the task on their own.

- The Helper does not do the task for the Finder, but rather helps the Finder learn and succeed. Give the Helper specific rules about what they can and can not say. For example, you may restrict them to “warmer/colder”. Or to asking questions such as “Where are you on the map?” “Is your map oriented?” “What do you see around you that matches the map?” “Where on the map are you going?” “Which way is that in real life?”

- Children are often better than the teacher at figuring out how to explain things to a struggling classmate.

- Spectator — Synonyms: Official, Timer, Counter, Cheerer, Supporter

- When children complete their activity while others are still on their course, you may give them the option of helping or spectating. Spectating encourages paying attention to others.

In a team orienteering game, members of the team may have various roles related to executing the task. One person may specialize in reading features on the map; another may ensure that the map is correctly oriented; another may keep track of time; another may make sure that everyone’s input is considered, and so on. Building a practice of naming roles sets the groundwork for these future games, and develops life skills for successful collaboration with others.

Maps tell you how to find things

Maps are a way for one person to tell another person how to find things. Some children will be able to understand maps easily, but others will struggle with map interpretation. Therefore, we start with other ways of communicating location and direction, before introducing the map.

The “warmer/colder” game allows communication of direction relative to a single point. The Red/Blue exercise allows communication of direction in two dimensions. Distance is introduced when you say how many steps to go in the given direction.

To emphasize efficient communication of how to find things, instead of timing the activity, try counting the number of instructions that the Clue-Giver gives, and reducing those. (A Spectator can do the counting!)

Timing individuals

There is a timing component built in to some of these lessons, and orienteering is normally a timed sport (similar to cross country, cycling, speed skating, etc.). Timing students as they participate is an excellent way to encourage them to develop their speed, improve their skills, and even practice their memory. It can also provide competition for students who are interested.

It is important to remember, however, that not all students feel comfortable being timed, especially when it’s a new activity they are still learning. Even when timing is used, it’s important to emphasize accuracy in orienteering as opposed to raw speed. Finding all of the correct checkpoints is just as important (if not more important), than finding them quickly.

Timing the whole class

Timing is also used to measure the success of the class overall. This is a very effective way of uniting the students, developing their teamwork, and emphasizing cooperation. In addition, it establishes the expectations that the students are working together as a class, and that every person’s individual actions can affect the group as a whole. It encourages the practice of helping each other learn.

Building a mental map — remembering where things are

Developing a mental map is a very important step in understanding the spatial relationships between objects. By learning and remembering a specific location, students are developing the areas of their brains associated with relative positioning, distance, and imagery, as well as memory itself. When they remember a location, they must recall information important for finding that specific point, such as which side of the room, whether is underneath or on top of something, and what other objects were nearby. While a visual memory such as this may not be a standard orthographic map, their brains are still creating a guide from one place to another based on spatial information.

Matching patterns on a map to patterns in terrain

Spatial pattern identification is the cornerstone of understanding map orientation. The concept is very easy, although it might take a bit of prompting for them to make the connection. It is generally helpful to start out with something simple, but also unique, such as the layout of cones in the Geometric Animal-O.

The important connection the students develop is the relationship between the layout of space and the layout of the map, specifically in how they match. Starting with something simple like a pattern of cones to help establish this connection is an important intermediate step between understanding a basic map and a full-scale orienteering map. As the layout becomes more and more abstract (like a real map), it becomes more and more of a challenge to establish this connection.

Orienting the map

Orienting the map is one of the most fundamental skills necessary for navigation, and for many students is also one of the most challenging concepts to grasp. On the surface this is very simple — the map matches the area around you, so hold the map in the same direction — but for a student whose brain is still developing its capacity to understand the relationship between objects, this is an incredibly confusing task. Make sure students who are struggling receive patient instruction where basic and distinct landmarks are used to convey distance and direction when orienting the map.

This is one area where using student Helpers can be tremendously useful. Students who recently acquired a skill will be better able to communicate the steps necessary for other students to grasp the same concept. It will also keep successful students occupied and interested, while students who struggle will receive the individualized attention they need to learn the skill.

Acknowledgments

Katelyn Greene of Cambridge Public Schools (CPS) is a co-author on the curriculum, linking our lessons to SHAPE America standards and provided valuable feedback. Jamie McCarthy, Coordinator of K-12 Health and Physical Education for CPS, arranged the opportunity. Tom Materazzo, a CPS PE teacher, was also part of the curriculum development team. Additional CPS PE teachers involved in piloting the program include Carlos Claros-Molina, Steve Lore, Evan Allen, Susan Harris and Mark Antonelli.

The first lesson (Boundary and Gathering) is based on USA Junior Coach Erin Schirm’s middle school lesson plans. Our approach and philosophy is strongly influenced by Erin. The second lesson (Animal-O) is based on reports from Andrea Schneider and David Yee about activities for children at European orienteering events. The orienteering lessons came out of curricula developed by Navigation Games in work from 2015 to 2019 with the Cambridge Community Schools JK-5 after-school classes (led by Barb Bryant, Ethan Childs and Adam Miller), and with JK-5 Physical Education classes at Cambridge Public Schools in the spring of 2018 (led by Melanie Serguiev, with Evalin Brautigam, Tomas Kamaryt, Marie Brezinova, Ethan Childs, and Adam Miller).

A previous four-lesson version was presented at the MAHPERD 2018 conference (with Amanda Klein and Cristina Luis). Many instructors and advisors at Navigation Games have contributed to creating and testing our lessons. We have drawn from the larger world of ideas for children’s orienteering — thank you all!